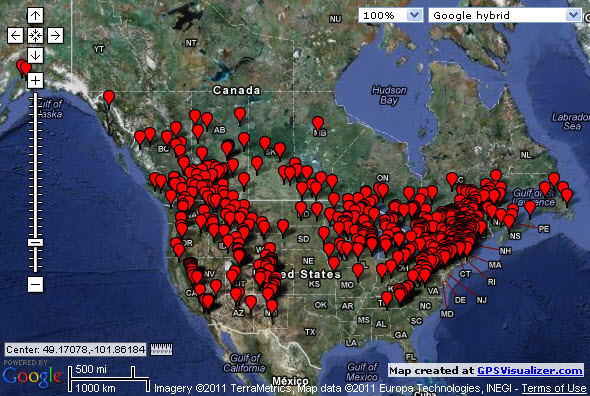

In the early 1990s, while working at Jay Peak, Vermont as a ski patroller, Marc Guido created an online insider’s guide to his adopted home mountain. With the worldwide web still in its infancy, Guido built on that electronic foundation to develop what could arguably be called the first full-service skiing website, First Tracks!! Online Ski Magazine (FTO), which continues to provide an extensive array of content, including daily news coverage, user forums, resort features, videos, condition reports, and a clickable map with the location of every ski area in the U.S. and Canada.

When a ski magazine has the words “first tracks” in its title, it’d normally be safe to assume that the person who edits and publishes it is living somewhere with convenient access to untracked lift-served snow. Since 2004, Guido has, in fact, been comfortably ensconced in his dream ski town, Salt Lake City; however, for the first decade of the website, he was based out of several locations that very few hardcore skiers would have called home. On a recent trip to Utah, I caught up with the founder and editor of FTO and got the inside story on his Road to Alta.

When and where did you start skiing?

As a young boy, I lived in Boulder, Colorado and began skiing at the age of 5. My father was the director of engineering for Head Ski Company, where he oversaw product design and development. After the company’s founder, Howard Head, sold it to AMF, most of the executive staff jumped ship. The president of Head took the same position at Thermos and brought my father with him; so in 1974, we moved to their headquarters in Norwich, Connecticut.

Which New England mountains did you ski back then and what do you remember of skiing in the 1970s?

I usually skied in southern and central Vermont: Killington, Bromley, Stratton, Mount Snow, Haystack, Magic Mountain, Pico. When I was in high school, I became president of the ski club and got to ski for free, so that was a nice little gig for me. Once every season, we’d go on a family trip to northern Vermont, which was something I always looked forward to.

I usually skied in southern and central Vermont: Killington, Bromley, Stratton, Mount Snow, Haystack, Magic Mountain, Pico. When I was in high school, I became president of the ski club and got to ski for free, so that was a nice little gig for me. Once every season, we’d go on a family trip to northern Vermont, which was something I always looked forward to.

Without going into “those-were-the-days” sentimentality, what I remember most from that era was that skiing seemed, for lack of a better term, purer. The lift-served hills were, generally, only in the business of skiing. There weren’t that many full-service ski resorts using real estate to prop up their revenue streams.

Was there a specific turning point when you transformed into someone who “lives to ski?”

The big breakthrough for me as a skier was in my early 20s. During my first job out of school, a couple co-workers and I drove up to Jay Peak for a weekend.

I met a patroller on the tram and showed her places on the hill that even she wasn’t aware of. She was impressed with my quasi “local’s knowledge” and suggested that I become a patroller. I looked at her and said, “I live in Boston! It’s a 3.5-hour drive for me with no traffic!”

That night, I was lying in bed and thinking that maybe it wasn’t such a crazy idea after all. I could drive up Friday night, stay somewhere cheap, and ski all weekend. The next day, she told me how to get involved and the following season, 1988-89, I went from skiing 20-25 days per season to almost 50.

I also found myself surrounded by people who were much better skiers than I was, so they paired me up with this guy named Sonny Cote to get my skills up to snuff. He was in his early 80s, had two artificial hips, and could still ski me into the ground.

At that point, did Jay Peak already have the reputation for big snow and extensive tree skiing that it does today?

The “Jay Cloud” reputation was around, but most people thought that it was just marketing hype. Remember, those were the days before electronic communications with real-time photos. All we had was snow phone reports, black-and-white newspapers, and print magazines, none of which provided an accurate assessment of current conditions.

When I first started working there, glade skiing still hadn’t caught on with the public, but as a patroller, I was quickly initiated into that culture. We would turn our patrol jackets inside out before going into the woods, and put them back on the right way after we came out. Another dodge was to have a non-patroller friend ski 100 yards ahead of us and we’d “chase” after him through the trees.

Had they already started putting glades on the map?

They were just starting to do that. In fact, my first year there, they officially marked a couple of woods shots. As you know, these days, half of Jay’s trail map is gladed out, including many of what were our private stashes back then.

What was it like to ski east-coast trees on 200-length planks?

That was state-of-the-art equipment at the time; we didn’t know any better. Only now do we realize how technology changes over the past 15 years have made skiing so much easier than it was back in the long-board days.

What were the origins of First Tracks Online Ski Magazine?

In the early 90s, I was a member of the Ski Vermont LISTSERV, an electronic mailing list application based out of the University of Vermont that, amazingly enough, is still in operation today in more or less the same format. LISTSERVs pre-dated the worldwide web by many years. At the time, the internet had been around in various forms (e-mail, FTP, etc.), but the web was still very much in its infancy — it was just unadorned machine text. Anyway, based on my experiences at Jay, I started posting what skiers now call “trip reports,” i.e. real-deal descriptions of what it was like on a given day.

The next step was to begin archiving this content so readers could click through it. I eventually dubbed these narratives “No-Bull Ski Reports.” That’s how the Magazine was born.

How did your days as a Jay Peak patroller come to an end?

In 1995, I got married to a woman from Montréal. Unfortunately, there were no professional opportunities for her in Vermont, and I didn’t want to live in Canada. I ended up getting a great job offer; the only problem was that it was based in, of all places, Florida. While living in a tropical climate wasn’t a life goal of mine, my wife was more than happy to move somewhere warm, so we relocated to the Sunshine State after the 1995-96 ski season.

How did moving to Florida affect the development of the Magazine?

Since I was no longer living in the northeast, I obviously couldn’t continue to post my Jay reports, so out of necessity I started collecting content about other areas as well. I figured that I could write a feature article or two, and maybe some other people could contribute as well. In fact, several people whom I knew through SKIVT-L eventually became contributing writers for the Magazine. Another important factor was the release of the Mosaic browser. Suddenly, it was like, “Wow, I can use different fonts and colors! I can add photos!” Even though it looks archaic to our eyes now, back then it really was a quantum step forward. Sometime around 1997, I renamed the site “First Tracks Online Ski Magazine.”

How many days did you ski each season while being based down there?

Around 30. All of those days were facilitated by the fact that I was researching articles for the Magazine.

Which other elements of the Magazine did you develop next?

We created user forums, which allowed readers to keep the concept behind the No-Bull Ski Reports going. At one point, we dabbled in supplying weather data, resort directories, and other products, but in the end, news content was our bread and butter and we eventually made a conscious determination to return to those roots. The lesson learned was that instead of trying to be all things to all people, it was critical to focus on what we did well.

How did you maintain your sanity living in a place with no snow?

Those destination trips gave me the fix I needed while I was stuck in that mosquito-infested swamp of a state. After eight years there, ski salvation appeared when my former company offered me an 18-month assignment in Albany, New York and I jumped at it.

After you returned to the northeast, did you consider going back to patrolling at Jay Peak?

I thought about it, but by then, the Magazine was taking up too much of my time. While those years at Jay Peak changed my whole ski universe, especially my desire for adventure and the feeling of camaraderie with other patrollers, there was no way that I could go back to driving 3.5 hours in each direction every weekend and volunteering 40+ days there per season.

1.5 years later, as my job in Albany was winding down, my wife and I started thinking about a new place to live. I obviously didn’t want to move back to Florida and she didn’t want to live in Albany. We decided that each of us would write a short list of places where we’d like to live. The location that was the highest match on our respective lists was where I’d start looking for a job.

Did your lists have any locations in common?

As you can imagine from what I mentioned earlier, my wife’s selections favored warm, sunny places in the southern half of the U.S. like Phoenix and Tucson. As long as I stayed clear of deep-freeze cities, I knew that we’d eventually land on a mutually-agreeable location.

What were some of your choices?

From a skiing perspective, a place like Jackson Hole was an obvious consideration, but you’re days from anywhere and unless you had bought a home there three decades ago, it was prohibitively expensive. A few places in Idaho and Montana were appealing, but they were too small or remote for our needs. Denver is a great city, but I’d be two hours away from skiing and four hours on Sunday nights with all the traffic on I-70.

Knowing how this story turns out, I assume that you’d already decided to lobby for Salt Lake City?

Absolutely. I had traveled there on a press trip with my wife the previous winter, and I knew that the quality and reliability of the snow there were second to none. It’s only 20 minutes from some of the world’s best skiing, but there’s virtually every amenity here, from cultural attractions like a symphony orchestra to being able to run down the street and get the latest electronic gadget to great dining. Where else are you going to get that combination in North America? Finally, I *knew* that Salt Lake City was going to appear somewhere on my wife’s list.

What appealed to you about the Salt Lake ski areas as a group?

In addition to having so many great mountains in such close proximity, the most impressive thing for me was that each one has such a distinct personality. Solitude has amazingly underutilized terrain. It’s named after a former mine up near the summit and it couldn’t be more appropriate. I don’t know anyone who’s ever waited in a lift line there.

While Brighton caters heavily to the local population and park aficionados, it also has great runs off the Great Western and Millicent lifts and offers excellent backcountry access. Snowbird is steeper than hell and has long fall lines. It’s big, brash, and in your face. Expert skiers who come to Utah and don’t ski there are doing themselves a huge disservice.

Park City provides something the Cottonwoods can’t: a walkable ski town. Some people not only want to make turns, they also want the whole après-ski experience: restaurants, boutiques, spas, etc. Since all three resorts are so close to one another, it doesn’t matter where you’re staying, you can just hop on the shuttle and ski whichever mountain fits your mood that day.

What do you think about efforts to connect the Cottonwoods ski areas with those in Park City?

I’m very much in favor of an interconnect. There’s great skiing on both sides of the Wasatch, and each could benefit from something the other has. People staying in Park City could take advantage of the Cottonwoods’ better conditions, more challenging terrain, and longer season, and the Cottonwoods clientele could enjoy Park City’s ski-town culture and the three resorts’ extensive intermediate trails.

The other part of the argument is that the Wasatch Front’s population is predicted to double in the next 30 years, and the existing infrastructure won’t be able to support two times the amount of vehicle traffic. Also, the Little Cottonwood Canyon access road has the most slide paths per mile of any road in North America. When the red snake of cars is inching up or down the canyon on a storm day, a decent-sized avalanche could take out 30 vehicles. An interconnect would substantially reduce the amount of congestion, pollution, and accidents generated by skier traffic. It’s win/win/win. Unfortunately, I don’t see it happening given environmentalists’ vehement opposition to any expansion beyond the current resort boundaries.

How would they link the various areas?

With the right land easements, you could connect all seven resorts with two relatively short chairlifts. There are proposals to enlarge existing mine tunnels between the Cottonwood Canyons and Park City to accommodate vehicles. A few are still being used today, for example, to transport drinking water. They’re also actively exploring a narrow-gauge cog railway to ascend Little Cottonwood Canyon and alleviate traffic on that road. In fact, last spring, a number of government transportation and ski officials flew to the Alps to review existing railways there.

Given how many great options there are from where you now live, why have you made Alta your home hill?

There isn’t a ski area in this region that I can’t recommend, but my heart is definitely at Alta. I’ve skied mountains with better overall terrain and more consistent vertical, but very few with Alta’s combination of terrain and snow. In addition, because many of the fall lines aren’t glaringly apparent, with a little bit of effort, you can always find nooks and crannies that are overlooked by even a lot of the regulars, who may prefer to ski the more obvious shots.

For example, there’s no way I’m going to score first tracks on “High Boy” on a powder day because the rabid 20-somethings will run me over getting there; however, if you really know the mountain’s topography, there’s always untracked snow that’s been overlooked by the masses. The people who are foaming at the mouth at 9 am will probably be on their way home by 11 because everything appears to be tracked out. Meanwhile, my friends and I will still be sniffing out untouched lines through mid-afternoon because we know how to get from Point A to Point B, or which way the wind was blowing, or what the sun was doing to certain aspects.

As anyone who’s skied with us can confirm, part of the fun is that every lift ride is a planning session on where to go on the next run and why. By the time we get off the chair, we have a pretty good idea of where to find the goods. Moreover, the decision-making process about where we’re going to ski on the next run isn’t monopolized by anyone in particular; each person puts in his or her two cents.

Finally, in addition to the things that you can measure, Alta has a really friendly, low-key vibe amongst the regulars. Even though you may not know each person by name, when you walk in first thing in the morning, everyone says hi to one another. That’s another reason it feels like home.

In the two or three times I’ve skied with your crew of expat East Coasters, I’m always impressed by how none of you get impatient with visitors who can’t keep up for whatever reason.

People from out of town are always saying “I’m sorry, I don’t want to slow you down,” but we live here, and the mountains aren’t going anywhere. There’s always tomorrow, or the next deserted midweek morning, or the following weekend. All of us have an extreme level of pride in what this region has to offer and we enjoy showing people around. It’s like living in a trophy house and we want to give our friends a room-to-room tour because we’re so proud of it.

Does the fact that you were based for many years in the northeast and Florida make you appreciate your current living situation, a 20-minute drive from Alta and Snowbird, all the more?

I’m not sure I’d put it that way. For me, skiing comes in many flavors. There’s ripping down frozen waterfalls on Mad River’s Paradise, slipping silently through eastern hardwoods on Hellbrook at Stowe, or laying down huge arcs on Alta’s Backside. I don’t look at one as inherently better than the other; it’s apples and oranges.

On the other hand, what all of these experiences have in common is that you’re using gravity to descend a mountainside with a couple of 2x4s strapped to your feet — how wonderful is that? That said, I don’t miss the -30F days one bit, nor the ferocious winds that follow any significant storm, nor the grey, blue, yellow, or green ice.

Anything negative to say about life in Salt Lake City?

Listen, no place is perfect. You’ll hear people grumble about suburban sprawl, strip malls with chain stores, and so on, but for someone whose primary interest is extremely reliable, high-quality skiing with a minimum of logistical hassles — in my humble opinion, this is it. Eight years ago, I couldn’t come up with a better place to live and I still can’t.

Credits

Utah photos courtesy of First Tracks!! Online Media. Snowbird photo by Matthew Fatcheric. Snowbasin, Alta Backside, and Powder Mountain photos by Robert Sederquist.

Jay Peak brochure/trail map provided by teachski.com.

Nice interview James.

I can also attest that he is a wonderful host to visitors and has learned all the places to go in any condition for the best turns and will happily take his guests to these stashes. I’ve skied dozens of times with him, yet I still don’t know how to get to some of these places.

James always brings the goods. Nicely done, cool read.

Nice photos. Lots of admiration for the way Mr. Guido made it happen WRT livin’ the dream. Curious, is FTO still an avocation or a full time gig at this point?