At 3 am on a Friday in early January, my taxi wound through the streets of Revelstoke, a town of 7,000 along the banks of the Columbia River in the British Columbia interior. A semi-overnight Greyhound ride from Vancouver took nine hours. Driving, the more reliable option, takes six. The nearest major airport, Kelowna, is 2.5 hours away and receives regular flights from Toronto, Calgary, Vancouver, San Francisco, and Seattle. In short, this is not an easy destination to reach from the U.S. east coast.

Red-eye bus-fatigue notwithstanding, I couldn’t help but marvel at the contraption working the graveyard shift: a tractor-sized machine sucking up snow and shooting it into a dump truck bin with the velocity of a wood chipper. This was a machine made for the Powder Highway, the swath of ski resorts and towns clustered in the southeastern corner of BC that never sees a dry season.

Two feet of snow had fallen at the beginning of the week — closing the highway to Revelstoke for several days, it should be noted, which can make chasing powder days from a long distance into a dicey proposition — and the town maintenance crew was still putting the finishing touches on their snow removal operation, which admirably left wide sidewalks alongside reasonably clear roads.

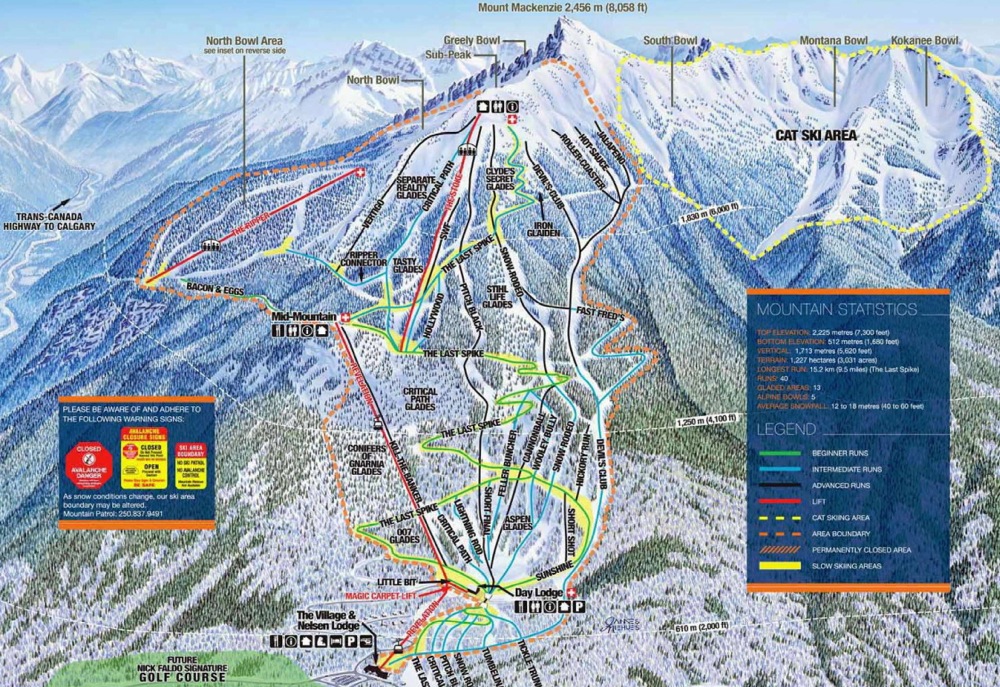

The morning wakeup call left no time for exploring town, however, as North America’s highest lift-serviced vertical beckoned just up the road with a whopping 5,620 feet of top-to-bottom runs. While ski resorts and their host towns rarely meet without a short drive in between, the ride from Revy the town to Revelstoke Mountain Resort (RMR) is under 10 minutes — less time than most Killington devotees spend on the Access Road or Lake Placid lodgers sit on the Whiteface bus. For $5 CAD round-trip, a regular shuttle makes the quick trip up to the mountain from most points in town.

I happened to just miss the shuttle and decided to throw out my thumb. Before long, a van stopped, piloted by a mangy Québécois puffing on a wooden pipe before work (tobacco, to be clear). He proudly recounted how his 1980s vintage Econoline, currently furnished with freecycled armchairs, once slept eight. Before I could get his backstory, however, the brief ride was over and it was “Merci, bonne journée” all around.

Revy has become a magnet for eastern Canadian skiers, including the legions raised on the Québec hills that mirror our cherished northeastern spots, not to mention the French-Canadian contingent that regularly flocks to Jay Peak. “We attract a lot of hippie Québécois,” laughed the French-Canadian proprietor of Mountain Meals, a local food spot serving up the home cooking that has made La Belle Province a culinary destination, albeit with recipes modified to accommodate a British Columbian winter larder.

Freshly deposited in the parking lot, I couldn’t help but notice the kindred spirits of my shaggy-haired chauffeur. A designated RV and camping zone at the far end of the lot was plenty busy with campers — both the vehicular kind and some hardy folks who had pitched tents. No doubt about it: Revelstoke revels in its hardcore reputation and the faithful flock accordingly.

That said, first-time visitors like myself are surprised to learn that RMR is a recent arrival to the Columbia Valley. In fact, the resort takes its name from the town but not from the mountain. The actual Mt. Revelstoke is itself a national park that begins just outside of town, while RMR is situated on the flank of Mt. Mackenzie, an 8,058-foot Selkirk peak. (In this corner of the continent, where ranges pile on top of ranges, the Selkirks, which start around Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, carve their way north between the Monashees and Purcells and collectively form the Columbia Mountains — these are not part of the Rockies.)

Revelstokers have been skiing Mt. Mackenzie since the early 20th century. Founded in 1885 as Farwell and renamed for Lord Revelstoke, the town boomed as a mining outpost and transfer point between the east-west Canadian Pacific Railroad and the north-south steamship line along the Columbia River in the days before hydroelectric dams, when a barge from Revelstoke could end up in Portland, Oregon before heading out to sea. This unexpected logistical hub deep in the mountains attracted immigrant labor, including Scandinavian stock who brought the first skis to the area. Locals called the skinny planks “Norwegian snowshoes” according to the Revelstoke Museum and Archives, which dedicates an entire exhibit to the town’s ski history and published a book, First Tracks: The History of Skiing in Revelstoke, in 2012.

The Revelstoke Ski Club celebrated its centenary last year and a 1928 article claimed that local kids go “out of the cradle and onto skis,” but Revy’s early claim to fame wasn’t downhilling. For decades, Mt. Revelstoke was known for its ski jump, the first permanent launch in Canada. It was so formidable that officials at times forbade competitions out of fear for the athletes. That didn’t stop local Nels Nelsen from setting two world records and having a newly built hill named after him.

Eventually, the ski jump fell into disuse as more modern facilities were constructed elsewhere, but the town mountain with a consistently steep pitch was too good to leave unskied. In 1963, a 700-foot towrope was installed and later a double chair ran further up the mountain. For town residents, including the locals with whom I shared my first gondola ride of the day, the old hill had the flavor of a small time Vermont operation à la the towropes and t-bars profiled in United We Ski. Unlike their northeast counterparts, however, there was a lot more mountain at hand along the Mackenzie cone that, until 2007, was the exclusive purview of cat skiing operations and backcountry skiers.

As the real estate boom of the mid-2000s reached a crescendo, out-of-town investors came knocking with a proposal to transform Mt. Mackenzie into the next Whistler Blackcomb, the wildly successful resort whose annual skiers visits dwarf the interior. While lying in the shadow of Vancouver puts it much closer to a major metropolitan area and airport, the maritime Coast Mountains that Whistler calls home can just as easily see rain as snow, while the Selkirks consistently receive the fluffy white stuff.

The ambitious plan came to half-fruition once the wizards of Wall Street nearly brought the global economy to a screeching halt. Revelstoke’s real estate dreams turned to dust, but were a blessing in disguise. The important stuff, namely the lifts, got built, as did a ski-in ski-out luxury hotel and enough base area infrastructure to graduate from town hill to proper resort. While providing a critical mass of shops, services, lodging, and eateries for those who want to wake up and click into their skis, this resort-lite — the opposite of the Whistler Blackcomb behemoth across the province — keeps the mountain access simple and effective. In turn, it spares its namesake town from too much competition that would suck the life out of the thriving small town business district and overly inflate home prices (though speculation did affect local rents and home prices, causing some grumbling among old-timers).

Only seven years into operations, RMR still feels brand spanking new, as though ski boots have barely scuffed the floors in the rental shop and guest services area. A one-day ticket will set an adult back $55 on weekdays and $61 on weekends — well below Intrawest’s flagship resort at the end of the Sea to Sky Highway. Moreover, reaching the top of Blackcomb’s one vertical mile requires a gondola to chair lift to chair lift to t-bar daisy chain that can run over an hour. At RMR, the state-of-the-art Revelation Gondola rockets 3,547 feet in elevation, followed by a short ski to the Stoke Chair, which deposits skiers just shy of the 7,677-foot subpeak, a brief bootpack away. Total elapsed time: 30 minutes or less. From there, a dozen-plus drop-ins to the North Bowl offer wide open powder options, funneling at the bottom to the Ripper Chair for ample glade skiing, or a traverse back over to the front side.

Three lifts is all it takes, a mantra to mountain minimalism that works surprisingly well. It provides access to varied terrain while also regulating skier traffic and avoiding congestion on the hill. Were the mountain ever busy by major resort standards, that could mean serious lift lines, but RMR’s relative isolation still only draws committed out-of-towners.

Locals, meanwhile, don’t chafe at powder-day queues. Alex Cooper, editor of the Revelstoke Times Review, told me that the early week powder day before my arrival — a major dump that finally put the entire mountain into play — required a 7:30 am arrival for anything resembling the 9 am first chair. The community plays by the rules, however. Just put your skis in line at the foot of the gondola and feel free to kill time grabbing a coffee in the café.

Unfortunately, the mountain was well skied out by the time I arrived several days later and also suffering from a rare temperature inversion that mashed up the snow quality at higher elevations. RMR’s monster vertical often results in variable conditions from top to bottom with a stubborn fog layer hanging mid-mountain that can make for a grey day in town but a glorious view at the top. The commanding vista of the Selkirks poking out of the clouds made up for the less than stellar conditions and offered a chance to eyeball the sidecountry and near backcountry options that make this area such a skier’s playground. But with several days of long uphill slogs ahead of me at Rogers Pass, I focused on the downhill at hand and happily put my quads to the test on a full top-to-bottom run as I pushed myself to ski the continent’s highest lift-serviced vertical in a single go. Needless to say, they burned most of the ride back up the mountain.

Taking full advantage of Mt. Mackenzie’s ample vertical and compact shape, RMR gives Revelstoke what it deserves: true big-mountain lift-serviced skiing close to home without destroying the unique culture and values of the town. A case in point could be found in the warming hut at the Stoke Chair crest, which is decorated with artwork by elementary school kids warning about avalanche danger, tree wells, and the perils of skiing without a buddy. On my way down, I emerged from the cloud layer and watched the town spread before me, knowing that the next generation to grace the ski movies of stoke lore was deskbound, counting the hours until the weekend of skiing arrived.

Hockey Night in Revelstoke

If the true measure of a ski town is its après options, then Revelstoke earns points for faithfully Canuck. During the day, a sign caught my eye at the gondola entrance: Grizzlies Game Tonight. Snow and ice go together like hot chocolate and marshmallows. In other words, ski and hockey seasons overlap, which meant the Canadian version of Friday night lights: minor league hockey.

The Kootenay International Junior Hockey League is not exactly an NHL pipeline like the Québec Major Junior League or the East Coast Athletic Conference, whose college hockey teams find their way onto hats and jerseys of skiers across the northeast. But for Revelstoke and the neighboring towns of the BC interior, it’s all they’ve got. So for $10 CAD a head, longtime residents watching their sons and in-for-the-season powderhounds looking for a cheap diversion piled into the Revelstoke Forum, a barn no bigger than the youth hockey arenas of my childhood but packed with trophies and memorabilia of beer league championships, Canadian Pacific Railroad tournaments, and a memorial to a local boy done good who punched his ticket to the big dance and landed a few seasons playing for the Vancouver Canucks.

“If we’re lucky there will be enough drunk ski bums to make this entertaining,” Alex told me as he snapped shots of the Revelstoke Grizzles vs. Castlegar Rebels showdown for the next edition of the paper. As luck would have it, there was more than a quorum of drunk ski bums. In the beer garden, a 19-and-over cordoned off section courtesy of BC’s wacky liquor laws, fans drained pints from local Mt. Begbie Brewery and tossed their plastic cups to the front where some animated ringleaders built a pyramid on the edge of the glass. Like a game of jenga, the pyramid tottered with every play in the corner that sent players into the boards. Protecting the temple became a sacrament as hands delicately propped up the unstable stack, until a Rebels goal celebration became a taunt: The scorer slammed into the boards intentionally and sent the plastic cup castle tumbling like a house of cards.

While the pyramid occupied most of the first and second period attention, cheers and jeers erupted during the third with no relation to the on-ice action. Across the rink, a fight had broken out and a couple of yahoos, including one wielding a crutch, wailed at each other until security successfully muscled them out. The Grizzles may have lost 4-2, but at least the game had all the elements of a Gordie Howe hat trick.

It Takes a Village to Raise an Idiot

Conventional après-ski options include a handful of bars, while nightlife is limited to a nightclub of familiar faces and a bowling alley. This is not the party scene of Whistler, nor does sleepy Revelstoke aim to be. With so much pow to ski, it’s often early to bed, early to rise. Outside of the resort’s luxury digs, lodging in town is simple, comfortable, and affordable. Lately, even the New York Times has spilled ink on The Cube, a Piet Mondrian-inspired boutique hybrid hotel/hostel with striking modern design that hints at where Revelstoke’s recent cachet may take it. Ditto for night owl gathering spot The Taco Club, bringing the food truck trend to small town late night eats and improves on it in a winter climate by leasing an adjacent indoor space with full bar.

The classic option remains the Village Idiot, where straight skis from the ’80s form high back chairs and quality pub grub fuels hungry skiers. Hockey Night in Canada comes early in Pacific Standard Time, with the first game at 4 pm — perfect timing for après. The NFL has been making steady inroads north of the border, however, and most TVs remained tuned to a Seattle Seahawks playoff game, as the recent Super Bowl runners-up command a big BC following. Alex and I managed to carve out a screen for the Montréal Canadiens — Habs fans being a rare breed in these western parts — while a scattering of Canucks and Calgary Flames gear suggested that Revelstoke was something of a sports fandom fall line akin to the Connecticut River’s division of Yankee Country and Red Sox Nation.

For Canadians, however, hockey is a default mode. Revelstoke is not by any stretch a hockey town, and in fact a young skier flirting with a cashier at Valhalla Pure Outfitters confessed he hadn’t been to a Grizzlies game when I asked how much tickets run. “I care more about skiing,” he said matter-of-factly. Browsing the latest gear and guides, or rummaging through the excellent second-hand options at Back On The Rack Sports Consignment, are just as popular as taking in some puck play.

If hockey is the national pastime, then skiing remains unquestionably the local one. Revelstoke is home to many who have made the sport into more than just a hobby. The roster includes photographer Bruno Long, ski mountaineer Douglas Sproul, pro freeskier Dane Tudor, and Big Bend custom ski maker Daryl Ross. Internationally certified mountain guides wander the streets of Revelstoke the way Nobel laureates lurk around Cambridge, Mass., and the amount of heli-ski operations rivals the number of colleges in Boston.

Revelstoke Mountain Resort is just the most recent cherry on top of the terrain that spills out in every direction from this interior BC hideaway. While riding lifts is great for quick powder day hits before work and playing it safe when the avalanche danger is off the charts, the ski culture of Revelstoke lives for more than resort skiing. In Revelstoke, the freedom of the hills constantly beckons, and nowhere more than up the Transcanada Highway at Rogers Pass.

Great read! This is now on the list of places to go. How was the travel times, accessibility getting there?

Really good article about my home town – I enjoyed it BUT … The ski jump was on Mount Revelstoke and not Mount Mackenzie. My dad was one of those early jumpers.

Thanks for the correction Chelan, edit has been made.