Unfair. This is the adjective that always comes to mind whenever I visit Salt Lake City, and my most recent trip there in mid-March was no exception. While pulling out of the parking lot at The Canyons in Park City after a great day of spring skiing, I considered the inequitable number of great options at my fingertips. Just a few miles away, I could do a Jed Klampett and rub shoulders with the rich and pampered at Deer Valley. I could circle around to the other side of the Wasatch Range and go to my favorite Cottonwood Canyons ski area, the aptly-named Solitude. I could head north to equally uncrowded Snowbasin or, if in a low-budget, no-frills kind of mood, keep driving another half hour and hit up Powder Mountain. And that didn’t even include hugely popular Snowbird and Alta, boarder magnet Brighton, bustling Park City, or off-the-beaten-path Sundance. Really, with ten first-rate ski areas within an hour or less of downtown, it’s hard to go wrong.

And easy to get spoiled. With all these choices just around the proverbial corner, most visitors find it preposterous to leave the cozy confines of the Salt Lake City region. It’s no surprise that the very few times locals manage to tear themselves away from northern Utah, it’s usually to go to places with lots of hike-to terrain like Jackson Hole, Taos, or Silverton.

I guess that’s why my itinerary for this particular Utah trip seemed a bit odd. Instead of heading west through Parley’s Canyon back to the city, I turned my electric blue Chrysler Cruiser down Route 40 through Heber City, alongside Deer Creek Reservoir and Provo Canyon, before heading south on I-15 past the central Utah towns of Nephi and Beaver, and several mammoth Flying-J truck stops. Though the route was lined by huge snow-capped mountains, the summer-like temperatures and dry, brown landscape in the valley made me wonder if I should have brought along my mountain bike on this trip rather than a pair of skis.

Finally, about four hours, one pound of roasted sunflower seeds, two Diet Cokes, and several Frank Zappa albums later, I pulled into the unassuming town of Parowan. In the fading evening light, I almost expected to see tumbleweeds bouncing through its deserted main street or a dustbowl blowing in from the nearby desert. However, while climbing up winding Highway 143, the landscape changed dramatically, as bright red cliffs poked through the edges of the steep canyon walls speckled with pine trees. It felt exactly like the two-lane road I used to drive to the gorgeous Jemez region of north central New Mexico, my favorite mountain biking area while a grad student in Albuquerque during the early 1990s.

By the time I arrived at Brian Head Resort, after climbing 12 miles through four separate climate zones, it was completely dark and noticeably colder. Winter clearly wasn’t over up here at 9,600 feet: the highest base altitude for any Utah resort.

The next morning, I pulled up the blind and took in the first of many gorgeous, wide-screen panoramas of white snow, red rock, green pine trees, and deep blue skies that I’d experience over the next 48 hours, with Navajo Peak in the foreground and Brian Head Peak looming directly behind it. Looking down at the parking lot, 10-foot snow banks towered over my car — a pretty fair indication that, despite its geographic position in the middle of the desert southwest, Brian Head was no slouch in the precipitation department.

After a nice buffet breakfast at the Double Black Diamond Steak House, I drove over to the base of Brian Head Peak, booted up, and following what has to be the shortest distance I’ve ever walked from my car to a main lift, got on the Giant Steps fixed quad chair for a leisurely ride up the mountain.

Once at the summit, I joined a dozen other people gazing out over one of North American skiing’s true money shots — a sublime mountain and desert vista encompassing the edge of Cedar Breaks National Monument with its stunning chiseled red rocks, the Kolob Plateau, the Pine Valley Mountains, Vermillion Castle, and the Tushar Mountains. I’m not sure which was which. All I know is that it was spectacular. And frankly, my photos do a pretty mediocre job of conveying this incredible view.

After several minutes of gaping, it was time to ski, so I headed down the Sunburst trail and spent the next two hours carving through perfectly formed spring corn.

The only evidence that the ski area, along with much of the region, had been suffering from a precipitation drought over the past few years was a sign at the base indicating that “only” 272 inches of snow had fallen this season — about eight feet below where they should have been at that time of year.

However, in spite of the sun beating down relentlessly on the slopes, there was great coverage on all of the trails off the Giant Steps chair, which cascade down the 1,300-foot vertical in a series of drops and flats like a big white staircase.

Although experts will find much of the lift-served skiing at Brian Head a bit tame for their tastes, with a short hike or a $5 Snocat ride they can head to the summit of Brian Head Peak to access an additional 400 vertical feet. Backcountry fans can park a second car along the access road to take advantage of terrain on the backside of the peak.

On my second ride up the lift, it occurred to me that most of Brian Head Peak’s frontside was oddly void of trees, with isolated matchstick pines dotting the slopes. When I mentioned this to the skier next to me on the lift, a local from nearby Cedar City, I got an earful about a once-every-500-years beetle infestation that, over the past decade, had decimated a majority of the beautiful spruce stands that dominated the ski area until recently.

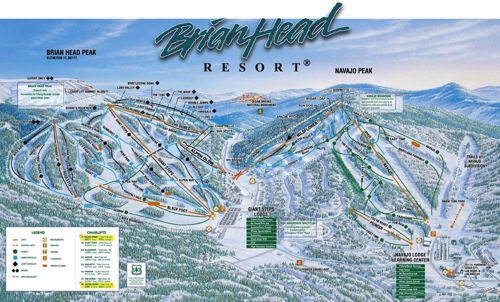

As we neared the summit, he pointed out several completely denuded sections that, he claimed, were so thick with trees a few years ago, you couldn’t even see the next trail over. The resort’s printed trail map (which clearly hadn’t been updated to reflect these changes) validated his story, as all of the runs depicted on the upper mountain were lined with thick sections of pines. The resort has valiantly replanted hundreds of new trees, both for aesthetic reasons and to act as a natural snow fence. However, it will be quite a few years before they’ll be big enough to make a difference. The upside to this situation, of course, is that there is more open terrain to be skied, particularly on powder days.

The next morning, I headed over to Navajo Peak, a separate beginner/lower intermediate area with a handful of long, easy trails covering 604 vertical feet, for the first chair at 9:30 am. Although it was Sunday morning, a time when the place should have been crawling with kids and boarders, I didn’t run into one other person for a half hour. Standing completely alone at the top of the Navajo trail soaking in that 360-degree view was, no question, one of the moments I’ll remember most about my season. Interestingly enough, the Navajo sector appeared to be comparatively untouched by the beetle invasion. As I glided down “Brave,” which was enveloped by a thick Spruce forest, I could see what Brian Head Peak must have looked like in the mid 1990s.

Brian Head makes no bones about the fact that a large percentage of its lift-served terrain is suitable primarily for novice and intermediate cruisers. And given the ever-present temptation to be distracted by the area’s jaw-dropping scenery, this may be a good thing. Although the ski area is located in the state of Utah, a large part of its clientele is tourists from Las Vegas, along with desert denizens from Nevada and Arizona, and suburban vacationers from southern California.

Since Brian Head can’t compete with Salt Lake City ski areas for challenge, terrain size, or ease of access, it wisely concentrates on promoting itself as an easygoing, crowd-free ski experience geared specifically to families; something that doesn’t really exist four hours to the north.

With its two separate sectors — one featuring nothing but beginner trails and the other with more intermediate fare — Brian Head is a perfect place for novices. By sticking to the mild trails of Navajo Peak, greenhorn skiers won’t have to worry about taking a wrong turn and ending up on an unexpectedly steep trail or getting flattened by an expert charging back to the lifts. And when they’ve progressed enough to take on more challenging terrain, Brian Head Peak is at the bottom of the hill.

Moreover, with the most expensive lift ticket topping out at an extremely reasonable $39, along with $10 Tuesdays, Brian Head is a bargain when compared to most other ski areas. It also provides an appealing alternative for powder hounds who don’t want to stand in long liftlines on big snow days.

It’s a shame that the Elk Meadows ski area, about 45 minutes to the north, has been closed for the past two seasons (and according to local scuttlebutt, may be done for good). Having two winter resorts in the region would certainly help create more of a draw for a southern Utah ski scene and benefit both mountains’ bottom line.

As much as I plan to come back to Brian Head for the skiing, I’d be just as happy to return during the warm-weather months for what must be some of the best mountain biking on the continent. With more than 200 miles of single-track trails covering 5,000 vertical feet, complete with roundtrip shuttle or chairlift access, I’m sure that the resort’s mountain bike park would be spectacular.

While I certainly understand why so few SLC-based skiers make the trek down to Brian Head, I was impressed enough by my weekend there to recommend it to anyone looking for a snow-sure, low-stress vacation getaway, especially if you can couple it with a trip to Sin City.